By Jeffrey C. Goldfarb, June 11th, 2013

Today I explore the relationship between Obama’s national security address with his surveillance policies. Many see the distance between his speech and action as proof of their cynicism about Obama and more generally about American politicians. I note that the distance can provide the grounds for the opposite of cynicism, i.e. consequential criticism. But for this to be the case, there has to be public concern, something I fear is lacking.

I am an Obama partisan, as any occasional reader of this blog surely knows. One such reader, in a response to my last post on Obama’s national security address, on Facebook declared: “your endless contortions in support of this non-entity make you look increasingly ridiculous.” He wondered: “Is this really what a ‘public intellectual’ looks like today?” I am not profoundly hurt by this. I am enjoying the one time in my life that I actually support an American political leader in power. I was an early supporter of the State Senator from the south side of Chicago and find good reasons to appreciate his leadership to this day. Through his person and his words, he has changed American identity, to the pleasure of the majority and the great displeasure to a significant minority. Obamacare is his singular accomplishment. He rationally responded to the most severe economic crisis since the Great Depression, despite sustained opposition. Perhaps he could have done more, but powerful forces were aligned against him. He has carefully redirected American foreign policy, cooperating with allies and the international organizations, engaging enemies, working to shift the balance between diplomacy and armed force. Obama has worked to move the center left, as I analyze carefully in Reinventing Political Culture, and I applaud his efforts even when he has not succeeded.

That said I have been disappointed on some matters, and I want to be clear about them here. In my judgment, the surge in Afghanistan didn’t make much sense. The escalating use of drones, without clear . . .

Read more: Obama’s Dragnet: Speech versus Action

By Gary Alan Fine, March 23rd, 2011

Tuesday August 10, 1948 was, as it happened, a turning point in American culture, a small moment but one of major significance. On this day, Candid Camera was first broadcast on American television. For over sixty years Candid Camera and its offspring have held a place in popular culture. The show, long hosted by Allen Funt, amused viewers by constructing situations in which unsuspecting citizens would be encouraged to act in ways that ultimately brought them some measure of public humiliation, documented by hidden cameras. These naïve marks were instructed to be good sports. “Smile, you’re on Candid Camera” became a touchstone phrase.

Perhaps the show was all in good fun; perhaps it contributed to a climate of distrust whereby citizens thought twice about helping strangers. Still as long as the show remained in its niche on television it attracted little public concern and less disapproval. Candid Camera was, one might suggest, beneath contempt. What happened for sure is that in time the use of hidden cameras has mutated. CCTV (closed circuit television) cameras; the tracking of citizens by governments and corporations, is so endemic to the modern polis, it has become unremarkable. Surveillance is not merely an obscure commentary by Jeremy Bentham or Michel Foucault, but a reality of which we instruct our children. These cameras are treated as fundamental to security. And perhaps they are.

Technology has its way with us. As cameras have become more portable and as video has become more viral, the hidden camera has become an essential tool of the political provocateur. At one point both law enforcers and investigative journalists (think Mike Wallace) relied on hidden cameras to catch the bad guys engaging in despicable acts. The scenes made for effective prosecutions and mighty television.

But today the offspring of the old show have run amok, shaking American politics. Hidden cameras are everywhere. And they are used in a fashion that is quite different from the civic-mindedness of the journalists of 60 Minutes. Today, secret puppet masters are not inclined to trap their targets . . .

Read more: Candid Camera Politics

By Daniel Dayan, January 25th, 2011

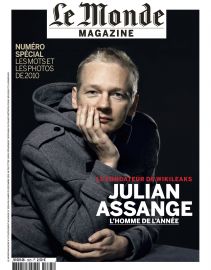

This is the first of a series of posts by Daniel Dayan exploring the significance of WikiLeaks.

Is WikiLeaks a form of spying? Transferring information to an alien power can induce harm. This is why spying constitutes a crime. In the case of WikiLeaks, the transfer concerns hundreds thousands of documents. The recipients include hundreds of countries, some of which are openly hostile. In a way WikiLeaks is a gigantic spying operation with a gigantic number of potential users. Yet, is it really “spying?”

Spying (in its classical form ) involves a specific sponsor in need of specific information to be used for a specific purpose, and obtained from an invisible provider. WikiLeaks “spies” eagerly seek to be identified (Julian Assange, WikiLeaks founder and editor in chief, has been voted Le Monde’s “man of the year”). Information covers every possible domain, and there is no privileged recipient. Anyone qualifies as a potential beneficiary of Wiki-largesses and most of those who gain access to the leaked information have no use for it. Spying has become a stage performance.

On 9/11 a group of Latin American architects hailed the destruction of The Twin Towers as a sublime event. The pleasure of seeing Rome burning had been made available for the man of the street. It was –suggested the builders – a democratization of Neronism. In a way, WikiLeaks, could also be described as a democratization of spying. It offers a form of “public spying.” Distinct from mere spying (a pragmatic activity), it proposes “spying as a gesture.” This gesture concerns other gestures. What WikiLeaks discloses is less (already available) facts than the tone in which they are expressed.

Content or gestures?

If the Assange leaks reveal nothing that we did not know already, what counts is less their propositional content than the enacted speech acts. The vocabulary of WikiLeaks gestures starts with the noble gestures of war. Many commentators tell the WikiLeaks saga in military terms. For the Umberto Eco, it is a“ blow:” “To think that a mere hacker could access the . . .

Read more: WikiLeaks and the Politics of Gestures

|

Blogroll

On the Left

On the Right

|